Doolhof

Tegen de top van de Hoge Berg ligt het Doolhof. Het perceel heette oorspronkelijk ‘Engelsteen’ en later ‘Engelse steen’. Dat heeft te maken met de grote steen die op het hoogste punt van de heuvel ligt. Veel mensen geloofden dat die steen helemaal door zou lopen, onder de Noordzee door, naar Engeland. Al in de achttiende eeuw werd dit verhaal ontkracht. Toen hebben werklui de steen helemaal ondergraven.

Lusthof

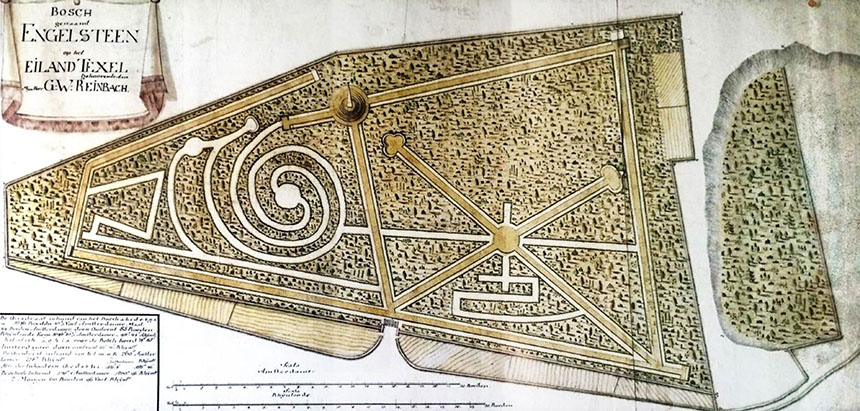

Cornelis Roepel was een hoge ambtenaar van de admiraliteit, zoals de marine toen werd genoemd. Hij kocht in 1764 het land rond de top van de Hoge Berg. Het perceel heette toen al ‘Engelsteen’ en was nog grasland. Roepel liet er een lusthof met een sterrenbosje met fraaie wandellaantjes aanleggen. Via een zichtlijn vanaf de top konden de wandelaars uitkijken naar de Reede van Texel. Oostelijk van deze zichtlijn werd een stelsel van rechte wandelpaden aangelegd, min of meer in een stervorm. De paden werden omgeven door hagen. Bij mooi weer ontving Roepel er zijn gasten.

De kuil

Voordat de heer Roepel eigenaar werd van het perceel is er in het oostelijke deel nog leem gewonnen. Leem is gebruikt om funderingen voor huizen mee aan te leggen. Door de eeuwen heen is hier zo veel leem gewonnen dat er een flinke kuil is ontstaan. In de verkoopakte van het perceel is opgenomen dat er geen leem meer verkocht of afgevoerd mocht worden. Dit mocht nog wel in het aangrenzende deel van het buurtschap; de Zandkuil.

Doolhof of Bossie?

Roepel liet westelijk van de zichtlijn een slingerdoolhof aanleggen. Via een spiraalvormig pad kwam de wandelaar in het centrum van dit bosje terecht om er via een ander spiraal weer uit te lopen. Je kon er niet verdwalen. Het was dus geen echt doolhof. Die term komt ook nog niet voor in de vroege verkoopakten, uit 1786 en 1794. Daarin is sprake van een ‘Bosje voorheen genaamd de Engelse Steen’. Texelaars spreken nog steeds van ‘t Bossie’.

Het oudste bos van Texel

Al in 1786 kwam ’t Bossie’ in eigendom van Texelse particulieren. In de loop van de negentiende eeuw was er steeds minder geld voor het intensieve onderhoud van de hagen. Men liet de bomen doorschieten. Op die manier ontstond een van de oudste bosjes van Texel. De aanplant in de Dennen en rond de Krim zijn veel jonger.

Vrij toegankelijk

’t Bossie’ werd in de loop van de negentiende eeuw een populaire plek voor de uitjes van de Texelse gezinnen. In 1840 kocht de gemeente het van de erven van burgemeester Reinbach. In 1966 verkocht de gemeente het aan Staatsbosbeheer. Dit met het uitdrukkelijke doel om de recreatiefunctie te behouden.

Zeven pannenkoeken

Van de ‘Engelse Steen’ gaat ook het verhaal dat het mogelijk een heidense rituele offersteen zou zijn geweest. Omdat men daar niets mee te maken zou willen hebben, zou deze zijn afgedekt met grond. Een extra bergje paste goed in het parkontwerp van Roepel. Het heuveltje werd gelegd in zeven gestapelde zandlagen. Dit zorgde voor het ontstaan van de naam ‘De Zeven Pannenkoeken’.

Herstelplan

In 2020 en 2021 heeft Staatsbosbeheer, de huidige eigenaar, veel van het oorspronkelijke karakter van de oude lusthof weer in ere hersteld. De zichtlijn van de top naar de voormalige Reede van Texel is weer open, net als de zichtlijn naar Brakestein. De wandelpaden, ook het slingerdoolhof, zijn weer open gesnoeid. Er is voor gekozen om geen nieuwe hagen aan te planten, maar de voorkeur te geven aan natuurlijke struikvorming. Ook zijn de zeven treden van de Zeven Pannenkoeken weer teruggebracht. Ringen van cortenstaal houden het zand op zijn plek. Dit roestende staal verwijst naar het ijzerrijke water uit de Wezenputten. Ook is de trap naar de kuil vervangen.

Stinzenplanten

Een ander onderdeel van het herstelplan was de aanplant van oorspronkelijke stinzenplanten zoals bosanemomen, boshyacinten, aronskelken en extra sneeuwklokjes. Eigenaren van landgoederen lieten lange tijd met een weelde van sinzenplanten graag zien dat ze rijk waren.

Boeren, Vissers en Buitenlui

Dit herstelplan van het Doolhof maakte deel uit van het project ‘Boeren, Vissers en Buitenlui’, gefinancierd door het Waddenfonds, StiftTexel en de Provincie Noord-Holland.